Welcome to this week’s edition of Cape May Wealth Weekly. If you’re new here, subscribe to ensure you receive my next piece in your inbox. If you want to read more of my posts, check out my archive!

Despite a continued rally in public markets, and a seemingly infinite supply of capital for anything AI-related, more and more of our entrepreneurial clients are starting to worry. Can the music keep on playing, and the rally keep on going? Or are we all just one event (think another geopolitical shock, a bad Mag 7 earnings report) away from a (seemingly) long-overdue market correction?

While I share this scepticism, unfortunately, I don’t have the answer to that question either (nor the crystal ball needed to find it). But what I can do is share our view on how we think investors should deal with these concerns - and what changes they can make to their portfolio in such times to sleep well again at night.

So if you’re like many of the entrepreneurs that we work with - heavily invested in public equities, crypto, and other risk assets, but uncertain whether to rebalance, and if so, how - go no further, today’s article is for you.

Setting The Scene

Most investors asking us about the ‘looming bubble’ are risk-taking entrepreneurs who sold their business (or had some other form of liquidity event) in the last 5-10 years and soon after proceeded to invest their capital in the market. Given that just 3-4 years ago we still had negative interest rates, most of their capital ended up in the aforementioned risk assets, such as public equities, crypto, or illiquid investments like venture capital, private equity, or real estate.

Admittedly, most of their investments have done well. The MSCI World has compounded at rates of 12-14% over the last 5-10 years. Tech indices like the NASDAQ, and its underlying stocks (esp. the Mag 7) have done even better, as have Bitcoin and many (but not all) PE/VC investments. Today, many of those investors are starting to be worried that their substantial gains might be wiped away by a looming market correction. Yet when it comes to making a change to their portfolio, they are hesitant - due to what we typically see as one (or multiple) of the following reasons:

They would incur a substantial tax hit. If you bought an MSCI World ETF 5 years ago from today, you would sit on an almost 100% gain. If you as a German-based investor were to sell, you’d take a substantial tax hit of roughly 9-10% of your position’s market value.

They see public & private equity as the most attractive asset classes. Given the long-term historical return, investors find it hard to justify shifting into asset classes with what they see as lower expected return.

They don’t know what else to buy. Perhaps they really are worried of a looming correction in US equities, and are willing to take the tax hit when selling. But where should that money go - cash? Other asset classes?

Yet despite these challenges, the investors that we talk to want to rebalance. Working with clients over the years during corrections such as COVID or this year’s “Liberation Day”, I’ve experienced firsthand that their fear of losing capital eventually far exceeds the fear of losing out on additional returns.

Hence, let’s take a look at all three of those reasons - and how we’d deal with them. As you’ll see, it is a multifaceted issue, but we’ll try to look at it from the most common angles.

Reason No. 1: Realizing Taxes During Rebalancing

We totally understand the issue: Whether they are fair or not, all of us would rather pay less taxes.

Taxes are easier to accept when you are selling a position due to lost conviction, for example buying a stock at its lows, seeing it reprice to ‘adequate’ levels, and selling out of it at a profit to redeploy elsewhere. However, things are typically a bit more complex for these aforementioned investors today. Most investors want to stay invested in their well-diversified ETFs for the long term, but simply want to reduce their exposure to be less affected during an eventual correction. And it’s the aforementioned looming tax hit that makes them hesitant to do rebalance.

The answer might be hard to accept: The right course of action might simply be to sell. As mentioned before, most investors end up being much more frustrated by a loss than taking money off the table too early. To share a personal story: During the ‘21 crypto hype cycle, I bought a crypto token for ~$5 that within just a few months rallied as high as $150 per token. But rather than sell at a tax hit, I was greedy, and wanted to wait for the 1-year mark, which in Germany would’ve made my token sale tax-free. That never ended up happening, as the token plunged as quickly as it rose - and while I still sold at a 5-6x multiple, I would’ve ended up with substantially higher profit if I had sold earlier, despite the tax hit. You live and you learn.

However, selling is easier said than done. Selling all of your position quickly falls into the territory of market timing, i.e. trying to sell all of your investment at the peak to repay it at a lower price (“sell high, buy low”). While a variation of this is part of our so-called risk management that we use in our client accounts, we’d greatly advise regular investors to be careful in trying to replicate such an approach - or as my ‘alma mater’ Goldman Sachs likes to stay, stay invested.

Instead, the much more approachable way of going about selling might be to rebalance your portfolio. For those less familar, rebalancing simply means selling and buying certain assets in order to bring your portfolio back to its target weights. After the strong equity rally of the recent years, most investors are heavily overweight in public equities - meaning that they would sell some of their public equity exposure to reallocate elsewhere in the portfolio, i.e. bonds, commodities, or cash. They might also rebalance within public equity, for example by selling some of their US exposure and buying equities in other regions of the world.

Yes, rebalancing does typically realize taxable gains, as you’d mostly sell assets that have gained in value. But it has two benefits in context of the problem at hand here: One, it is a great mechanism to automatically shift away from assets that have done well towards assets that either have done less well, and/or that might be more defensive. Two, if done regularly (and not just after incurring a 100% gain), it does split the incurred gains into smaller, more digestible hits.

And last but not least, to quote my co-founder and tax advisor Tamara: Don’t forget that taxes typically come in the context of a gain. So don’t see it as something to be unhappy about, but something happening in the context of something good.

Reason No. 2: Public (and Private) Equity As Most Attractive Asset Classes

When I ask why an investor is mostly allocated to public (and private) equity portfolio, I mostly get pointed towards the long-term return of equities. And it’s true: Since its inception in 1978, the MSCI World (in EUR) has generated an impressive return of over 10% p.a. Without a doubt impressive.

Most of the clients we work with tend to be younger (just as I am!), mostly having started their investment journey sometime in the 2010s, which has been an unparalleled time in the markets amid low or even negative interest rates and an overall accommodating environment for tech stocks. Hence, it’s not surprising that most investors might think that that performance will continue.

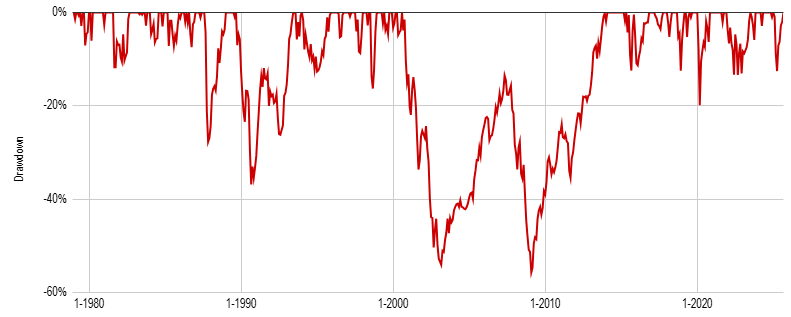

But in investing, it’s important to remember that there’s no free lunch. Long-term growth like this comes at a price - which in this case, is substantial volatility and risk. So let’s go back to another time, which (at least in terms of mood) might be comparable to today’s AI craze: the ‘99-01 tech bubble. Had you invested at the lofty valuations of late 2000, you would’ve been subject to a substantial drawdown of over 50% over the next 2-3 years:

Source: MSCI, Cape May. Historical performance is no indicator of future performance. Performance is calculated excluding cost and fees.

And that’s not all yet. After slowly digging your way out of your metaphorical performance ‘hole’ from 2003-2007, you would’ve then faced yourself with another (great financial) crisis, taking you even lower than during the aftermath of the tech bubble. Overall, it would’ve taken you over 10 years to be back at your prior high water mark. It’s worth noting that this is not a story of a single country, i.e. Japan, which famously took from September 1989 to September 2018 - over 30 years! - to reach its prior highs again. We are talking about the MSCI World - a globally diversified index of equities (sans emerging markets), and likely good proxy for equities as a whole.

But you might wonder - why should I care? You might likely be a young investor and might actually see a 10-year drawdown as a great opportunity to add more to your investment over time (i.e. dollar-cost averaging). But there’s a few factors at play here which we think speak against the 100% equities approach:

First of all, dollar-cost averaging becomes less beneficial over time. Unless your savings rate is going up substantially over time, it is unlikely that your additional dollar invested actually has an impact relative to many prior invested dollars. That doesn’t mean that dollar-cost averaging is a bad thing (especially from a psychological standpoint), but in our experience, it is simply not as meaningful as often assumed, especially once you are a few years into your investing journey.

Secondly, you might be unable to afford to sit out a drawdown. If you really are investing for the long term (i.e. you’re employed and putting excess savings to work in an ETF every month), you might admittedly be less affected by a drawdown - you can just wait and keep on saving. But things are different for many of our clients, who don’t just invest for retirement in 30-50 years, but need to draw capital from their portfolio to fund their cost of living. We like to call this path dependency risk: You might need to take money of out your portfolio while in a 10-year drawdown like the one above, which has you sell off assets at a likely loss (or at least a drawdown) to fund your expenses. As a result, your portfolio declines from performance while also declining from withdrawals - and all of a sudden, your hard-earned money quickly melts away. For income-oriented portfolios, 100% equities, in our view, is not the way to go.

Third, you might be able to sit out a drawdown - but will you? Especially in a world that’s moving more and more quickly, ten or even five years can be a long time to sit out. We’ve seen more than one investor throw the towel after been faced with a drawdown in one of their major investments (think crypto or tech stocks).

Just to be clear: Equities are an attractive, long-term oriented asset class. But unless you really are just investing for your retirement as an employee, it shouldn’t be the only asset class in your portfolio. Which brings us to our final section.

Reason No. 2: Unsure what else to buy

So you’ve followed our advice. You’ve understood that maybe taking money off the table, especially from some of your high-performing US tech equities, might be acceptable despite the tax hit. You’ve also understood that there might be assets beyond public equities. But like many of the investors you’ve spoken to, you might wonder - what else is there?

First, cash. Cash and cash equivalents can be a great diversifier relative to public equities. Asides from a default of the bank where you hold cash in excess of amounts protected by your local deposit insurance, cash in your base currency has essentially no price risk at all - which actually makes for a great combination with volatile public equities. (Of course it’s worth noting that cash is not risk-free - in particular, it is exposed to inflation risk. In many cases, your interest income (especially after taxes) might just be in line or even below the prevailing inflation rate in your region, meaning the real value of your cash erodes over time.)

By combining cash and equities, you can essentially build a portfolio that fits your individual risk-return characteristics in a given market environment (sometimes also called a Tobin portfolio). For example, let’s assume you are a EUR-based investor and your bank is offering you 2% interest on your cash. For public equities, you expect a 8% annual return and a 50% maximum drawdown - but you want to invest in a way in which your risk is limited to a maximum drawdown of 25%. By simply combining 50% cash (no drawdown) with 50% equities (max. 50% drawdown), you get your desired portfolio, at a simple average return of 5% (50%*2%+50%*8%) and a maximum drawdown of 25%.

Secondly, fixed income investments, such as bonds. Fixed income includes any investment that has a contractually defined return profile, such as a bond (split into defined interest payments as well as a defined repayment at the end of the instrument’s term). Bonds come in many shapes and forms, ranging from low in risk (such as US treasury bonds) to more risky (think high-yield bonds issues as part of private equity buyout transactions). They also vary significantly in geography (i.e. US, Europe, but also emerging markets) as well as issuer (from governments to companies to special purpose vehicles).

Many younger investors built their experience in the days of low interest rates and thus might’ve had little exposure to bonds. However, as interest rates have risen substantially and now stabilized at above-zero levels, they can be attractive additions to a diversified portfolio: Government bonds and/or high-quality corporate bonds might add stability in a way comparable to cash while also offering incrementally higher yield. Structured credit or emerging markets bonds offer higher yield through higher general risk, but also ‘differentiated’ risk (i.e. structural risks of structured credit or political risk for EM bonds). Lastly, investments like high-yield bonds offer returns that can be equity-like through a combination of high interest payments as well as repayment at values above the purchase price.

Especially riskier bonds are not a ‘beginner’s investment’ - they should be analyzed carefully to understand their risk and return expectations, especially in light of the current interest rate environment (hint: historical returns of bond ETFs mean little for today’s expected returns). But if done right, they can add a differentiated source of return without necessarily losing return as you would with cash.

Third and last, commodities. While most investors think of gold in this category, there are actually many more options out there - ranging from other precious metals such as silver to industrial commodities such as gold or even livestock. While each of these commodities differs substantially in its return, they all share one common characteristic, which is that they tend to do well in times of inflation. Professionally, I grew up sceptical of commodities (my alma mater Goldman Sachs didn’t like investing directly into commodities given the negative cashflow) - but changed my mind after 2022, when ‘safe’ bonds did even worse than equities while inflation-sensitive investments like gold or other commodities ended with positive returns.

As with bonds, commodity investments should be executed cautiously. Return profiles differ substantially from one commodity to another. Despite their role as ‘safe havens’, commodities like gold or silver are actually as volatile as small-cap equities. Lastly, many investors wonder if they should buy commodities like gold despite the tremendous rally over the recent months. But once again, commodities can be a fantastic diversifier - especially in times of geopolitical certainty and potentially higher and lasting inflation.

So going back to our original question - there are many asset classes that can be a valid alternative and/or addition to a public equity portfolio. But as with every investment-related matter, they should be picked prudently, and in light of your existing (as well as planned) other investments. It’s something we’ve done many times with our clients - so if you’re looking to diversify beyond equities, don’t hesitate - and reach out to us.

Liked what you read? If you enjoyed this piece, make sure to subscribe by adding your email below. I write about topics covering the world of family offices, asset allocation, and alternative investments.