Welcome to this week’s edition of Cape May Wealth Weekly.. If you’re new here, subscribe to ensure you receive my next piece in your inbox. If you want to read more of my posts, check out my archive!

Last year, I shared a series on LinkedIn outlining the math behind private equity (“PE”). One of the conclusions that I came to was that the often-used “IRR” metric in PE investing differs significantly from the cash-on-cash returns of public equities - and that investors need to ensure that they are being properly compensated for the risk and illiquidity in PE.

But that raises an important question: What excess return should PE generate over public equities? What drives this outperformance - is it the often-mentioned “illiquidity premium”, or another factor? And what additional risks should investors be aware of for this chance at higher returns?

To answer all these questions, I am happy to welcome Markus Derenthal as a co-author. Markus is the CEO of Excentrica, an investment firm he founded three years ago after his time at the University of Cambridge and Goldman Sachs in London. He advises Family Offices and helps entrepreneurs to achieve higher investment returns at lower risk compared to the standard offer of big banks.

Markus and I will do our best to answer thes questions we raised above - and of course, share our view on the matter. But before we can answer that question, let’s go back to how academia looks at stock performance.

Understanding the “Illiquidity Premium”

The very basis of risk and return is that if you accept a higher risk, you should expect a higher long-term return. Historically, the “Capital Asset Pricing Model” (CAPM) suggested that the performance of public equities can be explained by just two factors: the risk-free rate (i.e. the interest rate on “risk-free” cash or government bonds) and the equity market risk premium. Depending on whether a stock or a portfolio of stocks was more (or less) risky than the overall market, you could expect a higher (or lower) return.

Curiously enough, certain types of stocks performed continuously better or worse than suggested by the simple logic of the CAPM. More clarity arose through the discovery of so-called “factors”, including but not limited to Value, Small Size or Momentum, which could better explain stock performance. But beware: They can and will underperform for prolonged periods of time before they deliver you the desired excess return - they are called “Risk Premia”, after all.

This brings us back to the “illiquidity premium”: Pairing CAPM with those factors, we should be able to better understand the performance drivers of Private Equity. And if additional unexplained performance remains, it might be the elusive illiquidity premium, which is supposed to compensate an investor for taking on the risk of an illiquid as opposed to a liquid investment.

And indeed, some of the factors can help us better understand PE market performance:

Small Size Factor: smaller companies’ stocks outperform larger ones’, even when adjusted for their higher volatility.

Value Factor: cheaper stocks outperform more expensive ones. The PE industry is particularly focussed on low EBITDA multiples as a key measure.

Leverage: PE firms use borrowed money and aim to generate returns above the funding costs. This can boost returns dramatically, but equally increases risk.

Low, positive profitability: while not a traditional academic factor, Private Equity firms have shown a selection preference for companies that have low but positive earnings – leaving them room to grow profitability.

From a practical standpoint, this sounds right - PE tends to buy smaller businesses with more growth and optimization potential (“Small Size”, “Low positive profitability”). They usually do so at lower valuations (“Value Factor”), and often facilitate those transactions through the use of debt funding (“Leverage”).

But of course, we don’t just want something that sounds right in theory. We want real-world data to show us whether PE managed to outperform its public counterpart (and to ideally show if and when that will continue in the future), and how much risk those investments entailed.

From Theory To Practice (And Performance)

(As always, any comparison between asset classes should be “apples to apples”. PE usually reports performance as internal rate of return (“IRR”), which is based on a series of cash flows, whereas public equity performance is usually cash- and time-weighted. To make them comparable, you need to turn IRR into a cash- and time-weighted return, or you need to convert the public equity return into an IRR-like figure.

Academia has been tackling the question of PE’s long-term performance and risk, and two research papers stand out.

The first paper was published by investment firm AQR, in which they converted PE returns into cash- and time-weighted figures and compared them to its public counterparts. They show that from 1986 to 2017, the Cambridge US PE benchmark (which shows the aggregate performance of a large number of US buyout funds) posted a 9.9% p.a. return. During the same time period, the S&P 500 averaged 7.5% p.a. It’s an impressive difference, especially if assuming a 30-year compounding. However, the S&P 500 does not reflect PE’s bias for small, value stocks: AQR used the standard academic factors to construct a small-cap value strategy in public equities, which would’ve yielded average returns of 11.4% in the same time period - ahead of private equity.

The second paper comes from Harvard University and helps us answer the question of risk. They went to great lengths to analyze the almost 700 public-to-private transactions by PE firms from 1984 to 2017 in order to understand PE firms’ selection criteria and create a mimicking public equities portfolio. This way, they arrived at probably the most adequate risk estimates of Private Equity, yet: Using 2x portfolio leverage comparable to the analyzed PE transactions, their replicating public equity portfolio sees a volatility of around 27% and a maximum drawdown in this time period of -78%. Roughly twice the numbers you get for the S&P 500. (Harvard’s fictional portfolio also beat PE’s 11.4% p.a. net IRR by achieving a 14.8% p.a. net IRR).

There are two interesting take-aways from those two papers:

First, that PE success, on average, is less driven by operational efforts (i.e. the often-mentioned “value-add”) but rather by a focus on the aforementioned factors. One view to support this comes from Dan Rasmussen of Verdad Research, who invests into public equities according to a similar approach after he discovered during his time at PE giant Bain Capital that most of PE profits were driven by cheap deals, and not other factors such as management or company quality.

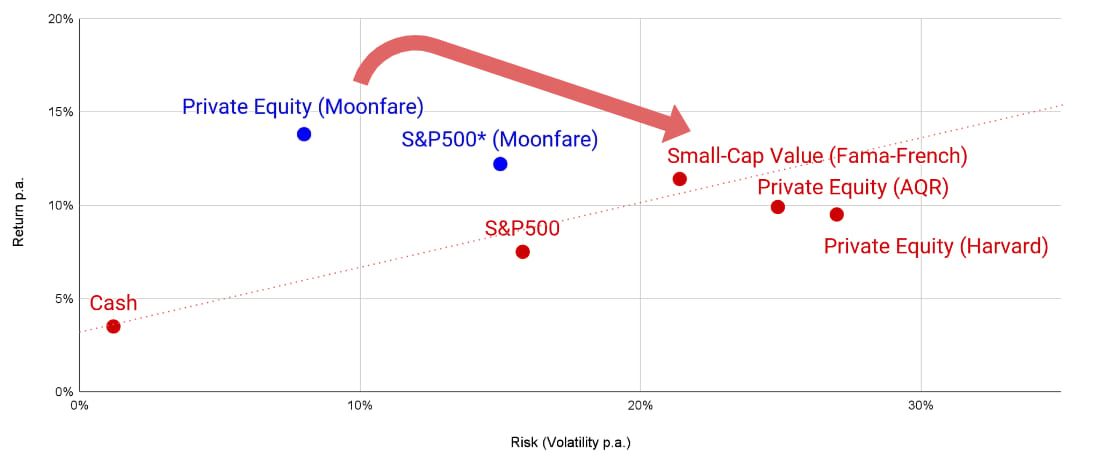

Second, that PE is much more volatile than many GPs say. Markus and I have seen more than one “chart crime” where GPs show PE as an asset class outperforming public equity with lower volatility - because they compare public equities with mark-to-market pricing with PE’s quarterly NAVs. The paper shows a more realistic figure, with volatility figures for PE that are approximately twice as high as public equities. Let’s compare numbers published by PE fund platform Moonfare with our previously mentioned figures:

Sources: Moonfare, Bloomberg, MSCI, Cambridge Associates, KKR, AQR, Kenneth French Data Library, Harvard Business School, Cape May Wealth, Excentrica. As of 12/03/2024. * Moonfare notes: “From 1Q86 to 4Q20 where data is available, deemphasizing 2008 and 2009 returns at one-third the weight due to the extreme volatility and wide range of performance, which skewed results. Using MSCI AC World Gross USD for Listed Equities; Barclays Global Agg Total Return Index Unhedged USD for Fixed Income; Cambridge Associates Global Private Equity for Private Equity; HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index for Hedge Funds; and Barclays US T-Bills 3-6 Months Unhedged USD for Cash.” For educational purposes only.

Of course, any backtest should be taken with a grain of salt. Consider the mentioned use of leverage: At a -78% maximum drawdown while invested into risky-small caps, most private investors would face margin calls or even get liquidated by their broker (which even the author admits). At the same time, maximum drawdown or changes in value matter a bit less in a loan to a PE-backed asset - as long as debt and interest are paid, your lender will always have an interest to work with you to see their debt repaid rather than push the company into default.

Nevertheless, we do have two sets of numbers that we can work with: AQR’s 2.4% PE outperformance p.a. for a time- and money-weighted return, and Harvard’s 1.8% PE outperformance p.a. on an IRR basis versus the S&P 500. And while both have shown that their respective replication strategies managed to beat those PE figures, we do get a partial answer to what we were looking for: That the average investment into private equity, historically, has managed to outperform its public counterparts.

But as always, things are not that easy. We’ve already outlined that PE is considerably riskier than public equities, standing at roughly twice the leverage of the S&P 500. We know that they use significant leverage. And we haven’t touched the question of fees, which some studies estimate at as much as 6% p.a. (split between management fee, carry, and portfolio-level fees).

So let us rephrase that question: What (excess) return should an investor expect from their private equity investment to be properly compensated for the risk that they take?

More on that next week.

Liked what you read? If you enjoyed this piece, make sure to subscribe by adding your email below. I write about topics covering the world of family offices, asset allocation, and alternative investments. And of course, follow Markus on LinkedIn as well.